US’ Innovative Grid Solutions: DOE releases pathway to commercial liftoff for advanced technologies

The US Department of Energy (DOE) has released its latest `Pathways to Commercial Liftoff: Innovative Grid Deployment’ report. This report is focused on identifying pathways to accelerate the near-term (3-5 years) deployment of key commercially available but underutilised advanced grid technologies or solutions, and their applications on existing rights-of-way (RoW) of transmission and distribution (T&D) systems. According to the report, deploying the advanced grid solutions could cost-effectively increase the capacity of the existing grid to support 20-100 GW of incremental peak demand when installed individually, while improving grid reliability, resilience, and affordability.

Figure 1: Summary of advanced technologies and applications under DOE Liftoff report

Source: US DOE

Amidst rising grid capacity demand from renewables, manufacturers, and data centres, the report concludes that the existing T&D system has untapped potential to help meet these challenges, which can be unlocked with a set of available technologies that are dramatically under-deployed relative to their potential value. These technologies can bridge the gap until new transmission, distribution, and generation infrastructure is built, all while maintaining grid reliability, resilience, and affordability. Grid operators and regulators should consider a new growth-oriented and proactive grid investment strategy to capture the value of these advanced technologies to meet customer needs within a changing energy future.

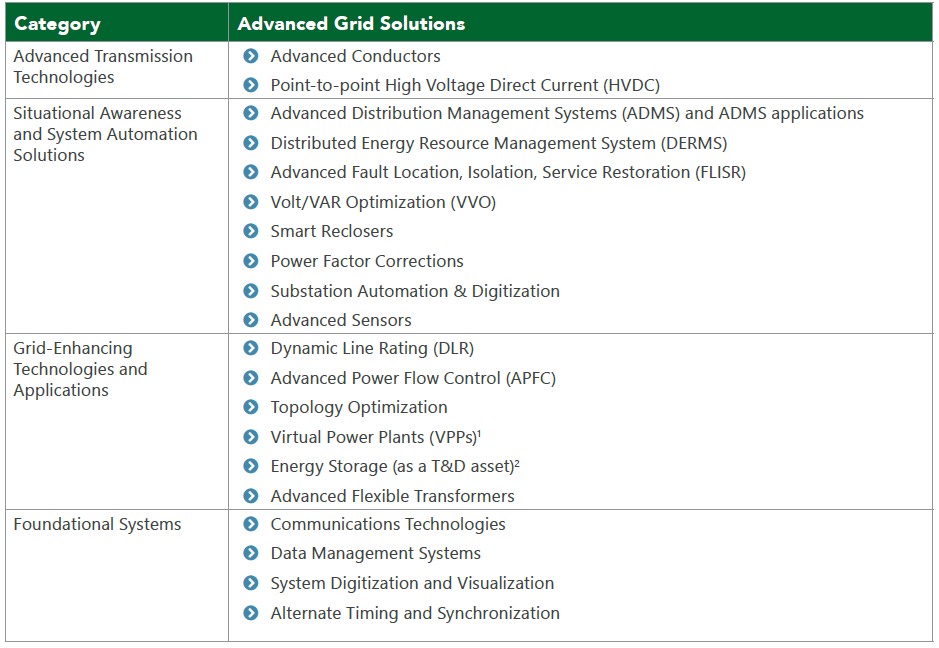

As per the report, multiple advanced technologies and applications are commercially available today that grid operators and regulators can use to help address near-term hotspots and modernise the grid to prepare for a wide range of energy futures. These advanced grid solutions include four categories that apply across the T&D system: a) advanced transmission technologies that expand firm line capacity, b) situational awareness and system automation solutions that improve visibility and decision-making, c) grid-enhancing technologies (GETs) and applications that improve system utilisation and performance, and d) the foundational systems necessary to enable advanced technologies and a modern grid.

Figure 2: Overview of advanced grid solutions

Source: US DOE

Collectively, these technologies, if deployed at scale, can provide a step change in grid operators’ ability to efficiently and effectively manage the grid. Grid operators can deploy these solutions in a variety of strategic combinations to address local needs as no single solution will suffice. A strategic, long-term (10-15+ years) investment approach is necessary to realise the optimised benefits between many of these technologies and to determine required foundational infrastructure investments that can fully unlock the benefits of future technology deployments.

Figure 3: Advanced grid solutions’ value proposition for key grid outcomes

Note: HVDC – high-voltage direct current; VVO – volt-var optimisation; ADMS – advanced distribution management systems; DERMS – distributed energy resource management system; FLISR – advanced fault location, isolation, service restoration

Source: US DOE

Most of these solutions could be deployed on the existing grid in under three to five years and are lower cost, greater value, or both when compared to conventional technologies or approaches. For example, dynamic line rating (DLR) can be scaled in fewer than three months after initial implementation to increase effective transmission capacity by an average of 10-30 per cent at less than five per cent of the cost of rebuilding the line to expand capacity. The applicability of these technologies varies based on local climates, operating contexts, and grid objectives. In some situations, deployment of advanced grid solutions can replace or indefinitely defer traditional grid investments; in others, these technologies serve as a “bridge to wires”, allowing better alignment between near-term customer needs and the cadence of grid capital planning.

These advanced grid solutions are already being used to drive system benefits. Many utilities, from large investor-owned utilities (IOUs) to small co-ops, are investing in and relying on these solutions for day-to-day grid operations. Adoption to date has largely been driven by policy or regulatory mandates, reactions to external pressures (for example wildfire risk, distributed energy resource adoption), or individual technology champions.

Yet deployment at scale is lagging across the US. Traditional cost-of-service IOU business models have not sufficiently incentivised these solutions to warrant the significant upfront planning, engineering, operational, and organisational effort required to deploy advanced technologies at scale. For smaller municipal utilities and electric cooperatives in particular, the upfront cost and organisational resources necessary to drive effective investment can be a particular challenge.

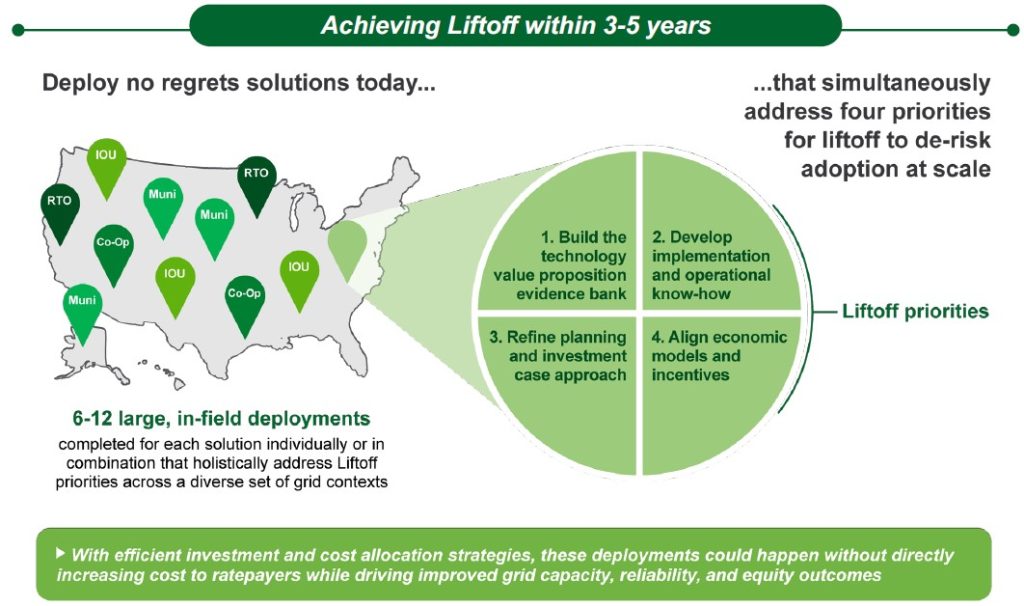

Liftoff will be achieved when utilities and regulators comprehensively value and integrate advanced solutions as part of core grid investment, planning, and operations. When these technologies are fairly evaluated and compensated, alongside the conventional options used today, utilities and regulators can ensure the most efficient and effective solution is used to meet customer needs.

Achieving liftoff within three to five years is possible by deploying 6-12 large operational, no-regrets deployments across a diverse set of utility contexts for each advanced grid technology— deployed individually or in combination. Four priorities should be simultaneously addressed during these deployments to derisk and drive adoption at scale.

Figure 4: Achieving liftoff for advanced grid technologies and applications

Source: US DOE

Cost allocation

Through more efficient and equitable investment approaches, grid operators and regulators can start deploying these advanced grid solutions without increasing costs for residential ratepayers. For example, using just one-fifth of the current conventional asset replacement investments to proactively upgrade assets with advanced grid solutions would double industry-wide investment in advanced solutions while improving grid capacity and reliability outcomes without adding costs to ratepayers. This represents an important opportunity to bring in new sources of capital by leveraging existing investments more efficiently and pursuing innovative cost allocation strategies. All utilities, states, and regions can begin developing proactive, forward-looking grid modernisation strategies to enable better prioritisation of and investment in the grid solutions that can best serve customers amidst a changing energy future.

Challenges and potential solutions

Many of the required solutions to deployment challenges have been or are being developed but are not yet widely adopted. Liftoff will require a combination of dissemination of existing and the development of new solutions in several areas. The following summary of challenges and potential solutions are being discussed in the report.

Figure 5: Summary of key challenges and potential solutions for liftoff*

Note: The list is not exhaustive

Source: US DOE

Conclusion

This report highlights the near-term opportunity to unlock untapped grid capacity opportunities and progress modernisation priorities with available advanced grid solutions on existing infrastructure. It is meant to inform and advance partnerships between DOE, other public sector stakeholders, and the private sector to accelerate near-term investment in these grid technologies and applications. Sustained action will be required to simultaneously scale up the adoption of commercially available advanced grid solutions, build new grid infrastructure, and deploy next-generation grid technologies.

|

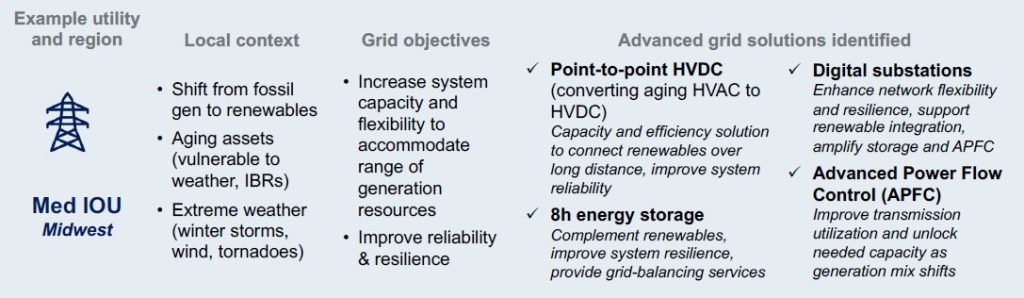

Hypothetical examples of adopting advanced grid solutions Example in practice 1: Medium IOU (Midwest) Note: IBR – inverter-based resource; HVAC – high-voltage alternating current; HVDC – high-voltage direct current In this hypothetical example, the state regulator, in collaboration with the regional independent system operator (ISO), identified a long-term need to improve regional grid reliability and resilience amidst increasing extreme weather and to integrate additional low-cost generation resources to replace retiring fossil assets. The local medium-sized IOU developed an integrated system plan to identify investments that would effectively and efficiently achieve these objectives based on its local context, existing assets and capabilities, and customer needs. In this scenario, the Midwest IOU identified a set of advanced grid solutions that met these long-term objectives while driving near-term value. For example, instead of replacing several ageing long-distance transmission lines with like-for-like high-voltage alternating current (HVAC) lines, the IOU identified that these lines could be converted to a point-to-point high-voltage direct current (HVDC) system to increase transmission capacity, efficiency, and improve system reliability and resilience with greater renewable penetration and extreme weather. The utility proposed energy storage as an attractive resilience measure along with digital substations, which can better integrate storage as a distributed energy resource. This package could improve reliability by providing short-duration contingency power during peak load times and interruption events. In the future, storage coupled with new renewable generation could be used to address demand growth. These reliability improvements and potential increases in distributed generation could defer the IOU’s T&D capacity needs to varying degrees. Additionally, advanced power flow controls and digital substations could enhance and optimise the existing grid’s utilisation and reduce line overloading, thereby effectively increasing transmission capacity in certain situations. Example in practice 2: Large IOU (Southeast) Note: VVO-volt-var optimisation In this hypothetical example, the large IOU was starting to see increased curtailment of low-cost energy generation due to a lack of sufficient transmission capacity. This was causing increasing congestion costs for ratepayers as gas-fired peaker plants were being deployed instead of the lower-cost renewables. In this setting, a conventional cost-of service compensation model can skew the financial incentive of the utility to choose higher capital expenditure (CAPEX) projects over more cost-effective solutions, as utilities receive a rate of return on approved CAPEX. Although a low-cost solution like DLR could reduce congestion by unlocking effective capacity headroom on existing transmission lines, the cost to deploy DLR on several lines at roughly USD10 million would only generate USD1 million in return on investment (ROI), which is often less than potential earnings from more expensive CAPEX alternatives (for example new transmission, asset replacement). Thus, the IOU may not prioritise DLR if congestion is not an imminent reliability threat and the investment brings limited financial value under current regulatory frameworks. The IOU can continue normal operations with gas-fired peaker plants serving demand. The resulting higher energy costs would be passed to consumers while the IOU pursues other investments (e.g., new transmission). When using a proactive, comprehensive, and customer-centric investment approach, the IOU identifies DLR as a viable low-cost option to reduce congestion costs. This comprehensive assessment identified additional benefits, including deferred transmission capacity cost, avoided congestion cost, and reduced greenhouse gas emissions. In total, this deployment could drive USD450 million in total value for customers over the 12-year investment period assessed—including USD100 million in total avoided congestion costs. The state Public Utility Commission (PUC) recognised the need to align the IOU’s incentives with customer outcomes. The PUC established a shared savings mechanism where the utility could receive 25 per cent of the value of the USD100 million reduced congestion costs. This translated into USD25 million in financial incentives for the utility, with USD75 million in benefits still going to customers through lower energy costs. This USD25 million incentive (significantly higher than the USD1 million return the IOU would have seen under conventional cost-of-service regulation) motivates the utility to prioritise DLR. |